I’m on a train from Sintra (best city I’ve ever visited) to Porto without wifi, which means I can’t watch the film I need to in order to finish up the next column for your 2025 rookie drafts. But I wanted to write something, and since I try to market this column at the intersection of economics and fantasy football I figured I would take the low hanging fruit.

As always — a warning: if you only want football content from this page, feel free to simply click off this post. I promise you a 2025 Running Back breakdown within 48-72 hours.

For the rest of you, here’s what today is all about.

I want to discuss tariffs in a plain language fashion that I hope will make the current state of the economy a little easier to understand — and do so without the condescending snark I will freely admit to adopting in my tweets on the subject. Then — just for fun — we’ll intersperse some dynasty applications along the way.

IMPORTANT NOTE: I am not an economist. There are countless journal articles and studies from much more impressive and knowledgable folks who know far more on this subject than what you’ll ever get from me. As such, this column is of course not financial advice. But I know enough to be dangerous on these matters — I studied economics in university prior to law school with a focus on global political economy, and in particular international trade.

The ironic part of this discourse climate is that during my undergrad, I was a (stereotypically) radicalized lefty infatuated by heterodox professors in the department, and I frequently sought out courses and literature which pushed back against the free-trade dogma you are constantly confronted with in introductory courses. The fact it’s now the ostensible right wing pushing a more aggressive protectionist regime than existed in 1930 is quite jarring for anyone who spent much time in an economics department.

While I’ve evolved in my views from the 21-year-old version fresh off reading Kapital, I am by no means a free-trade absolutist with a ‘Neo-liberal globe emoji’ in my twitter bio. I strongly believe that the government has a role in setting the economic agenda for a country, and should — at times — consider economic policies aimed at achieving domestic or international political goals, notwithstanding their potential impact on the stock market. That being said, the ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs are not an effective or revolutionary instrument to re-invigorate American industry to the highs of the New Deal era. While that’s how they’re being sold, in truth this policy programme appears to be an attempt to return to the Gilded Age via mass wealth redistribution.

Let’s go step-by-step.

What are Tariffs?

In short, Tariffs are a tax paid by firms which export goods into the tariff-levying country.

Let’s say the country of Apple-Land imposes a 20% tariff on orange imports from other countries. John from Orange-Town typically sells his oranges to grocery stores in Apple-Land for $0.50 per orange. Now, he has to pay $0.10 for each orange to the Apple-Land government.

John has two choices: he could — in theory — keep selling his oranges for $0.50 per orange while absorbing the tariff into his profit margins. In the short run he may be forced to do this, but in the long run he will likely either charge $0.60 per orange he exports into Apple-Land or export his oranges to a different country without tariffs.

Gocery stores in Apple-Land will either keep buying oranges from John — and charge more to consumers to cover the increased purchasing cost, or will simply stop supplying oranges.

As mentioned above, the effect of increased costs to import oranges will be either more expensive oranges for Apple-Land consumers, or a shortage of oranges altogether. This aspect of the column is not controversial.

If you read an article which claims companies will simply keep exporting tariffed goods into America at the same prices, you are reading pure cope. This might be true in the short run because American importers won’t necessarily be willing to pay an increased purchase cost to cover the tariff, and affected exporters cannot find alternative buyers in other countries for cheaper over night. But in the long run, they will find those buyers, and American (or Apple-Land) importers will either have to pay higher prices or cease importing.

So why would Apple-Land do this?

Increased import costs are not an unfortunate side effect of tariffs. It is the intent of tariffs. If we assume Apple-Land is acting rationally, the reason to impose tariffs is to incentivize Apple-Land grocers to buy oranges grown in Apple-Land itself, rather than import oranges from elsewhere.

Companies act in the interest of their shareholders, not the national interest. If you’ve ever seen Roger & Me, you know that ‘American’ car manufacturing companies have — over time — closed down domestic manufacturing plants because it is cheaper to produce cars in foreign locations where labour costs are lower. In theory, imposing tariffs on automobile imports will offset that difference in labour costs and re-incentivize auto-manufacturers to build more cars in the land of the free.

In sum, tariffs are a tool which increases the cost of importing goods to increase the competitiveness of domestically produced goods. Definitionally, this means consumers of those goods will have to pay higher costs for them.

What is a Trade Deficit?

Tariff proponents often bring up the size of the U.S.A.’s trade deficit. The formula upon which the latest round of tariffs is based is rooted in U.S.A’s trade deficit with each country.

In fact, the ‘reciprocal’ tariffs are not reciprocal in the strict sense of the word. The U.S. is not imposing tariffs equal to (or even correlated to) the tariffs imposed upon them by other countries. Instead, tariffs are being imposed in proportion to the U.S.A.’s trade deficit with each affected country.

By calling these reciprocal tariffs, the Trump administration is implying (LINK) that trade deficits are the result of being ‘ripped off’ by other Nations, or some other nefarious action taken against the U.S.A.’s interests. This is not (necessarily) the case.

Imagine two dynasty teams in a very imperfect metaphor.

Teams 1 is a highly competitive team, while Team 2 is a rebuilder. Team 1 is high-value and can buy almost any player in the market if they’re willing to put together a package, but has very few of their own picks because they’ve been focusing on maintaining a competitive roster, and trading picks for star players in recent seasons.

Team 2 however has very few star players but an excess of picks.

Team 1 is much like the U.S.A. They don’t have many domestic industries which produce cheaply acquirable goods, but they do have an abundance of star players (highly developed industries) and the capacity to trade for (import) whatever they need from elsewhere.

Team 2 is a developing Nation. It has very little capacity to trade for expensive players (import expensive goods), but does have an abundance of draft picks (domestic industries with cheap labour costs).

While Team 2 appears to be on the right track, there is no doubt you would rather be Team 1 in this scenario.

Trade deficits are not inherently bad. The primary reason trade deficits exist is because a country’s labour force earns high enough wages that it becomes cheaper to import products from elsewhere than to pay your own workers. While jobs leaving is not desirable, this is a good root problem to face — it means workers in your country are able to demand high wages.

Meanwhile, those same workers are able to buy cheaper goods than could be produced domestically because of imports from other countries.

When do Tariffs Make Sense?

Some orthodox economists will tell you that tariffs are (almost) never advisable economic policy. I don’t entirely agree, and for the benefit of readers looking to get a better picture, I will present a (realistic) steel man case for why, when and where tariffs make sense.

The first reason tariffs can make sense is in the context of international conflict.

If you take comparative advantage to its extreme conclusion, every country would be better off producing only the goods it can make most cheaply relative to all other countries, and then purchasing all other necessary goods via trade.

If you could reasonably expect every other country to act in good faith, this would be the optimal strategy. However, you cannot.

Both the Trump and Biden administrations levied tariffs against China, and I think that was at least directionally sound policy. America (and all of NATO) has a defensible basis to prevent China from becoming a global economic hegemon. While levying tariffs on Chinese imports have increased the cost of goods, you can reasonably argue that weakening China’s economic position (and strengthening the position of yourself and your allies relative to China) is a trade worth making.

A natural analogy is my favourite game — Settlers of Catan. If Daniel is at 9 victory points and is offering me one wheat for one brick, I might be better off trading 2 brick for one wheat from Ryan, who is at 6 victory points. While it’s more expensive for me, I would rather pay more to strengthen mine and Ryan’s position relative to Daniel who is about to win the game.

Another aspect to consider is fear of becoming reliant on importing goods in case those goods for whatever reason cease being offered to you.

Imagine an inactive dynasty league with few managers willing to engage in trade discussions. You might be willing to reach in the rookie draft for a given position of need because you cannot dependably trade at market value to fill needs later on. You’re best off building a self-sustaining team, even if you’re occasionally sacrificing market value along the way to do so. After all, what’s market value worth in an inactive market?

In sum, if you cannot trust your trade partners to continue to supply you with goods, or you do not want those trade partners’ goods because they may benefit to an unacceptable degree, you may prefer to pay higher costs to produce goods domestically or import them from a friendlier source.

There is no doubt America is currently facing headwinds in international relations, but these are headwinds of its own making. The U.S. Dollar is currently the reserve currency, America has a dominant and inter-connected economy, and strong military and economic alliances all across the globe. There is no reason to expect an un-provoked geopolitical conflict against America in the near future — in particular by its ostensible allies, and thus no incentive to decrease reliance on imports from those allies. If anything, a rationally-acting America should be encouraging imports from NATO allies to strengthen its bulwark against Russia and China.

The second logical reason to impose tariffs is to promote the development of a given industry.

As alluded to with the Apple-Land example off the top, if you want to produce a given product domestically and are currently unable to do so at competitive prices, increasing the cost of imports will compel domestic companies and consumers to buy domestic products instead.

Why is that an important goal?

Well one reason is if that industry is particularly strategic. Let’s say the government identifies a particular industry as key to the future economy, or decides that production of a given product will dovetail with its ability to potentially produce essential military equipment if necessary in the future. Imposing tariffs on the import of those specific products will help produce more of them domestically.

In theory, by artificially increasing the market share of domestic producers in the industry through tariffs, you will eventually stimulate the industry in a manner that makes it more efficient over time, and more competitive on its own merits in the long run.

However, tariffs are just one option to accomplish this goal. The CHIPS Act for instance was an attempt to develop semi-conductors domestically through government stimulus. The Biden administration pursued a similar directive with respect to electronic vehicles, passing stimulus initiatives which incentivized car companies to produce more ‘EVs’ and do in the United States.

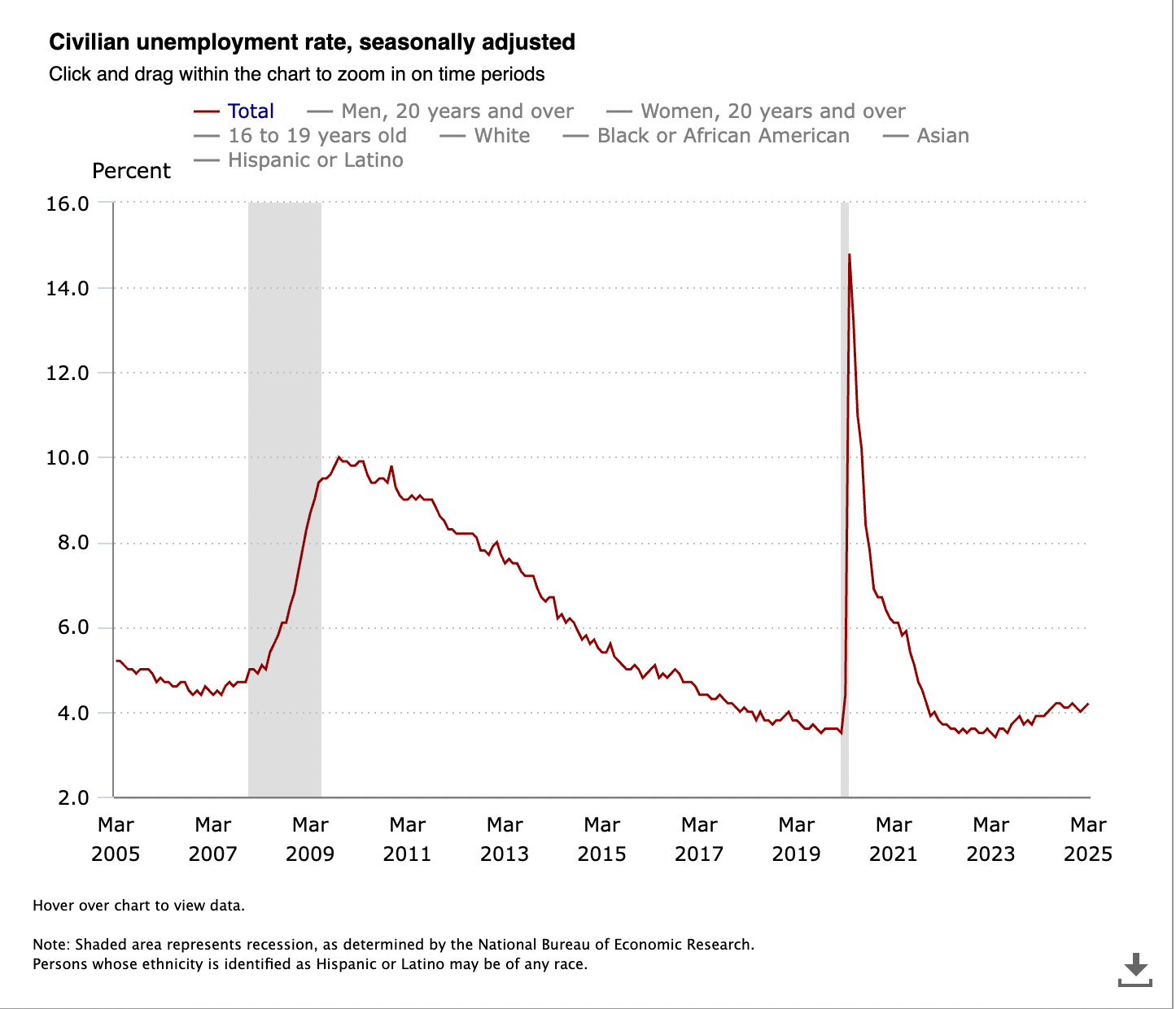

Another consideration is your country’s employment rate. If a country is losing jobs because firms are departing for cheaper labour markets, you may decide it’s worth absorbing cost increases for consumers in order to reduce unemployment. However, America is not facing a crisis of unemployment. Unemployment — despite a slight increase in the last year — is lower now than at any point in the previous 20 years and beyond, and is ranks strongly among developed countries which do not enforce conscription.

Pro-tariff commentators have argued that even though America is near full-employment, it’s worth pursuing tariffs to change from a “service-based” economy to a “re-industrialized” economy. Unfortunately, this goal has little economic merit.

Let’s assume for sake of argument that manufacturing jobs are in fact better-paying jobs than service-based jobs, and let’s also assume the average American would prefer to work in a factory at marginally higher wages than work a less-labour intensive office or service job.

For what it’s worth, both of these assumptions are quite questionable in 2025 — and I find it ironic how many people making these claims are venture capitalists who have not seen the inside of a plant in their lives.

In this scenario, Americans are earning higher wages, but the cost of the products they are manufacturing at these factories now cost more money. Similarly, since you are not creating new jobs but merely transferring workers from the service economy to the manufacturing economy (due to low existing unemployment), service industries such as restaurants, retailers, and ride-share vendors will have to contract their offerings to account for a reduction in available labour. As such, costs will increase due to reduced supply of these services.

So what would this get you? Yes, some workers have more money. But the cost of goods and services are higher, and services are less available. Any effect of workers’ wage increases are cancelled out by the inflationary effects of tariffs on the cost of living. More importantly, the tilt from a service-abundant economy to a manufacturing-based one with no increase in the labour force will decrease quality of life.

This is why broad spectrum tariffs without a tailored industrial focus or goal make no sense in a highly-developed country such as a America. Especially because when you apply broad spectrum tariffs on everything and every country, you will wind up increasing the cost of component parts so much that the specialized industries you may actually want to promote become even less competitive.

It is one thing to adopt tariffs in a developing country with high unemployment and extreme wealth inequality. You are creating jobs where none would otherwise exist, and the inflationary effect on the cost of living is — at least arguably — cancelled out in the aggregate by a material reduction in unemployment.

Furthermore, in many of these countries, there is a much smaller percentage of the labour force that is highly educated and working in ‘professional’ fields. Therefore, skilled-manufacturing exists higher on the scale of desirable and well-paying fields.

For a developing country, imposing tariffs may be a plausible avenue to develop industries that could not otherwise succeed, reduce unemployment, set up important industries to be more self-sustaining in the long run, and provide a pathway for more workers to generate sufficient income to support their family’s education in the future.

Think once again about two dynasty teams. In a vacuum, all draft picks are of equal value. But we know in realty that the draft picks of the lowest value teams will be higher in the draft and have more value later on. Low-value teams should ‘protect’ their picks from any trade negotiations in order to increase the value of their team when the picks convey. This situation describes a developing nation adopting tariffs to protect its own industries.

It would be nonsense for a high-value dynasty team to arbitrarily refuse to deal its own picks, which are likely to be late in the draft. If anything, such teams are better off trading their own picks for those of weaker teams. America engaging in protectionist economic policies is equally irrational.

For developing countries, tariffs may provide an initial boost into a different tier of economy. For America, tariffs are simply an inflationary doom loop attempting to solve a non-existent problem.

Tariffs, Income Tax, and the Deficit

This is my final point and it is the most critical one. The ‘Trump’ Card I see raised in favour of the administration’s tariffs is the possibility that tariffs will provide the government with revenue it can use to pay down the national debt, and eventually tariffs will replace income tax as the primary source of federal government revenue.

The first part of this is theoretically possible, but will not come at a palatable cost. Yes, the government can use tariff revenue to reduce the deficit and debt, just as it can tax revenue. But as we described earlier, tariffs do not produce ‘magic’ revenue.

The tariffs necessarily result in increased costs of goods and services. As such, they are essentially a sales tax paid in a different form.

Whenever you hear someone say that tariffs can be used to pay down the debt, they are just saying that sales taxes can be implemented to pay down the debt. This is not a revolutionary idea, every government raises revenue (or at least contemplates the potential to raise revenue) via sales tax.

The notion that tariffs will replace income tax is thus akin to saying that sales tax increases will replace income tax.

This is very bad policy for you unless you are a billionaire!

The U.S.A. employs a progressive taxation system. This means that as your income scales upward, you pay an increased rate of taxation on each dollar earned above a given threshold.

But even if America converted to a flat tax system, the richest Americans would still pay more in raw tax dollars because they earn far more money (20% of $1 Billion is much more than 20% of $50,000).

Sales taxes are regressive. The richest people spend a far lower percentage of their money on goods and services than the middle-class, and especially the poor, and place a larger portion of their money into savings and investments. Therefore, a far higher percentage of a poor person’s net income will be subject to sales taxes than a rich person’s, because a higher portion of their income will be utilized in sales transactions.

If the primary means of taxation in America were sales tax, the richest people in the country would actually pay a much lower percentage of tax than the poorest people in the country.

This is the America Donald Trump and his venture capitalist backers want. It would be a return to the gilded age which pre-dated the great depression, and in which money funnelled to a handful of aristocratic families.

The folks who are behind these tariffs are perfectly content to create a poorer country, with a depressed stock market, and increased costs of goods and services. They can merely shove their net worth into bitcoin, and make speculative bets on a turbulent market while ‘buying low’ before an eventual recovery. They’re not playing the same game you are. The best analogy to these people is the dynasty manager who trades draft picks years in advance to win leagues, orphans their team and refunds their future seasons though leaguesafe as soon as the worm is about to turn on their team.

If you are not one of these people — if you are a person who spends a high portion of the money you make, and depends on what savings you have to save for a home or retirement — this framework will not work for you, and I hope you take whatever political action you can to protest against it.

Back to football soon — see you later.

For those who seemingly got the wrong message from my non-partisan headline and who don’t follow me on Twitter …

My stance on the tariffs is opposed 😅

Very nuanced writing here Jakob. The intent seems there, if only the focus was narrowed to select industries and trading partners. The rhetoric used to support blanket tariffs seems well off. One can only hope that even those rusted on see that this isn’t the way.